Why I write...mostly

In my first post on Substack, I offer some thoughts on writing and why I do it, with help from two of the best to ever scribble.

When beginning a new venture, it’s usually a good idea to ask some good questions. In my case, that venture is starting this Substack and the first such question is, “Why?”

Nobody has ever asked me why I write. They’ve told me they’ve read my work and have enjoyed it, disagreed with it, concurred with it, and felt disengaged or depressed by it. But nobody has ever asked me why I do it.

No one ever peered over their coffee cup and said to me, “Of all the creative and professional endeavours available, why this one?”

As it’s a question nobody has ever asked me, and since I’m going to be asking for support to help me do it better, I thought I’d better get myself in order and try to answer it.

So, me, why writing?

To find an answer, I decided to turn to the place I do most of it. That deceptively organised vortex of books, papers, magazines, coffee cups, and whisky tumblers that I call my desk.

Currently, a copy of And Yet, a short collection of essays by Christopher Hitchens, sits next to my keyboard. Its bright green cover has phrases like, “The Sunday Times Bestseller” and “He could not pen a dull sentence if he tried,” on it. The latter praise is taken from a review in The Guardian and both accolades are well-deserved.

A target sits in the middle of the cover, a series of concentric black and white circles with a few arrows dotted about. Anyone familiar with Hitchens’ work, particularly his quarrel with the man the people of Rochdale have just elected to represent them in Parliament, George Galloway, will no doubt pick up on the relevance of having a close relative of the popinjay on the front of this collection.

Hitchens’ work features heavily in the bookcase that sits behind my desk. I keep his and other writers within easy reach for rest, inspiration, and provocation, depending on what I need at the time.

I admire his writing for many reasons. He’s funny; a trait many writers convince themselves they have, but only themselves. He’s cutting, clever, and a combatant. He observes the rules of good writing but knows that, per the guidance of his great subject George Orwell in Politics and the English Language, one should, “break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.”

The point is, he’s an inspiration of mine. He is not a “hero”, a title he objected to and, presumably, would not want.

Christopher Hitchens probably never held a copy of And Yet. He died in 2011 and it wasn’t published until 2015. Another volume, A Hitch in Time was published earlier this year. The same doubtlessly applies.

I never met Hitchens but wish I had. If that had happened, I am largely certain of what I would have said to him. After asking him to sign my copy of Letters to a Young Contrarian, I would have thanked him for expressing, in part, what I had only previously felt until then. My reason for being a writer.

During an interview, the author of The Trial of Henry Kissinger and The Missionary Position: Mother Theresa in Theory and Practice explains that it is important to ask oneself, “Has it ever occurred to you that you have no choice but to write?” Later in the same discussion, Hitchens mentions seeing the eyes of a student in his class light up, “as if to say, how did you know that?”, citing that as proof that the student was indeed a writer and didn’t just want to be one.

Hitchens further answers the question, “Why do you write?”, elsewhere by asserting that being a writer isn’t what he does, it’s what he is. An important and illustrative distinction for those careful enough to pick up on it.

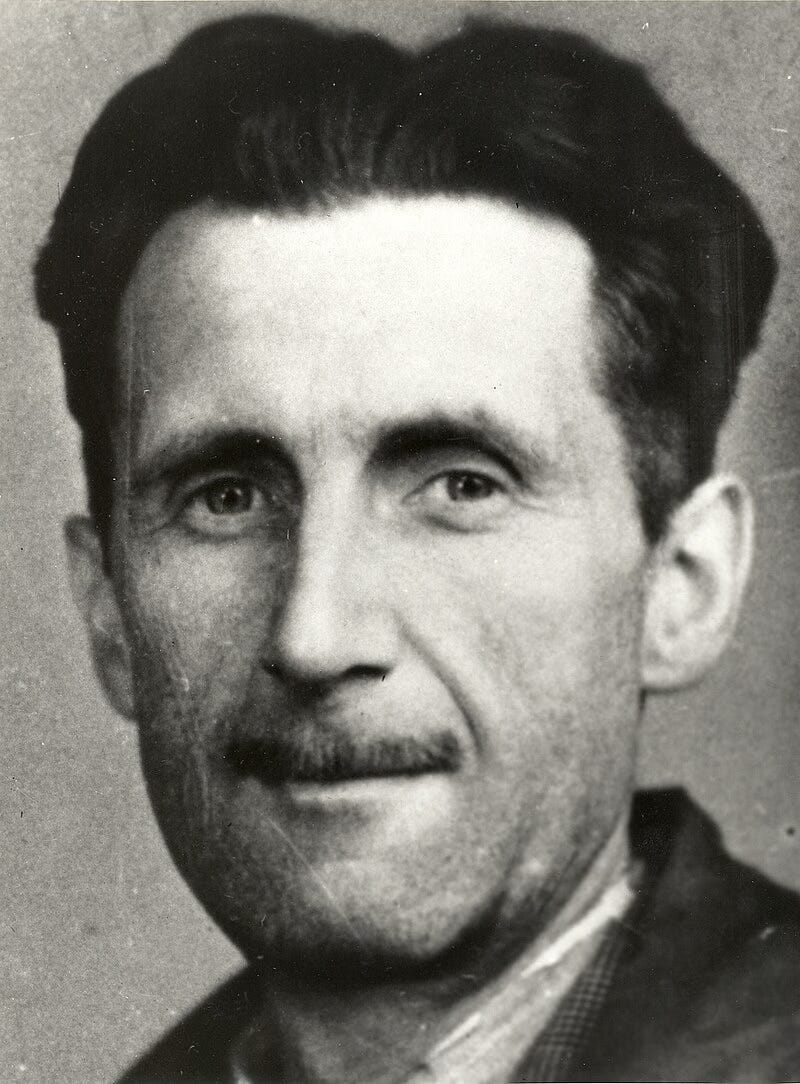

Venturing into the trove of literary jewels and finery left to us by Christopher Eric Hitchens results inevitably in finding some of George Orwell’s rubies and sapphires dotted around. This is true in the case of answering the question of why to write.

Orwell, in his 1946 essay Why I Write explains that there are four “great motives for writing.” The first of these is “sheer egoism,” defined as a “desire to seem clever, to be talked about, to be remembered after death, to get your own back on the grown-ups who snubbed you in childhood, etc.”

Next is “aesthetic enthusiasm,” succinctly defined as “pleasure in the impact of one sound on another,” followed by a “historical impulse” to scribble.

Orwell concludes his list with his strongest and most disputable claim, that all writers have some kind of “political purpose.” It’s hard to imagine Stephanie Meyer or E.L. James writing with such a purpose, at least not if “purpose” is to mean “deliberate.”

Why I Write is robust, intelligent, and under-read, true of most of Orwell’s milieu except for the two books whose titles I don’t even have to name. If you’re here, you know them.

It is also a balanced and careful work. Orwell points out that while he believes firmly that the four impulses are always present in the writer, they vary between, and also within, writers. He is correct to do so.

He’s most likely correct on the other points too. Individual writers may have additional compulsions or conceptualise the same drives differently but Orwell’s four points are a pretty damn good synopsis of the reasons to write or the reasons for writing. I’m still unsure if there is a difference there or merely a distinction.

The question of “why writing?”, returned to me when I decided to open up this Substack, as I have seen so many of my seniors do.

For now, I intend for it to be a source for my writing on whatever topic grabs my attention as well as a place to keep all the columns that esteemed titles like The Times, and especially the Scottish Daily Express, allow me to publish.

If there is such a thing as a regular “Alan Grant reader” out there, and I might be flattering myself in hoping that there is, I hope that they will enjoy this as a resource to read and share my work. It would mean a tremendous amount to me.

My answer to the question, “Why writing?”, may well take me some time to find fully, if I ever get there. For now, there’s a healthy amount of Orwell’s four impulses and a generous double measure of Hitchens’ assertion that I can’t not write, having done it in one shape or form since I figured out which end of the pencil makes the mess. I assume I’ve gotten better since then.

Brevity is a quality I admire, so in terms of a definite answer, I’ll go for a four-word one.

“Why writing?”

I’ll let you know.